In her 2020 memoir, Other Girls Like Me (Bedazzled Ink) Stephanie Davies tells of her coming of age in a small village in England, her anti-apartheid activism as a teenager, and her growing awareness of feminism and her queerness at Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp. This women-only activist space was set up in front of a United States military base in the south of England to protest the siting of American cruise missiles on British soil. September 2021 marks the 40th anniversary of the peace camp, which lasted for several years and attracted thousands of women. It served not only to protest nuclear war but provided a safe space for women, and particularly queer women, in a women-only community freed from patriarchal norms.

By Stephanie Davies

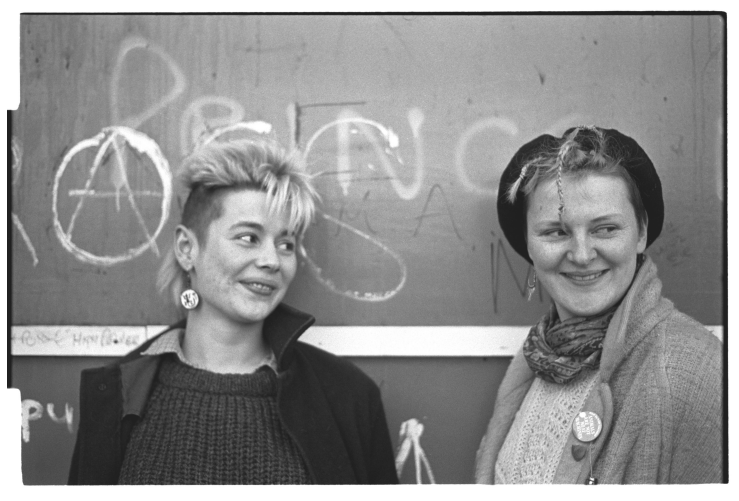

The feminism I read about in magazines when I was at university— the sexual revolution of women in the 1960s wearing mini-skirts and popping the pill, of 1970s braless hippie feminists in their flowing, flowered skirts—was nothing compared to the androgynous tribal freedom of Greenham. Whether we were lesbian, straight, or bisexual, we shocked wherever we went because we did nothing to conform, please, or titillate. England had never seen anything like us. We didn’t shave our legs, our armpits, or our pubic hair. We didn’t pluck our eyebrows or wear nail varnish. We wore men’s clothes if we liked, and we often went topless at the camp, or at least some of us did. We were altogether natural, except, of course, for our multi-coloured hair, which we wore as though we were our own tribe of Amazonian women. The freedom we felt in our own company was matched in intensity only by that of the looks, taunts, and rage directed at us whenever we stepped out into the “real” world.

In the following excerpt, Stephanie is living full-time at Blue Gate, one of the encampments set up at the entrances to the military base, which the women have named after the colors of the rainbow. She tells of her first encounter with Al, a punk rock singer in a girl band, a meeting that will change her life.

I WAS SITTING alone at Blue Gate drinking tea and gazing into the fire one sunny afternoon, when a tough-looking woman with a stiff red Mohican, Doc Marten boots, a black army surplus jacket, black jeans, a red armband, and a mischievous laugh, set herself down next to me, put out her hand to shake mine, and said, “Hi, I’m Al. Who are you?”

I already knew who she was. Rumours had been circulating around the camp for days that Al, a bass player in a two-girl anarcho-punk band called On the Rag, was coming to stay for a few days—and she fitted the description perfectly. Friends at Blue Gate had swooned a little just at the mention of her name, so of course, I was curious. I learned that On the Rag played at all the anarcho-punk venues around the country, supporting such legends as The Poison Girls and The Nightingales, espousing causes like the Miners’ Strike and Workers Against Racism, and sending their primarily female audiences into fits of pogo-ing as the two of them raced maniacally around the stage, spitting savage feminist lyrics and freedom songs into each other’s faces. They had two records out. My heart pounded as I told Al my name. She took my hand in hers, and instead of shaking it, she put it to her lips and looked gallantly up into my eyes.

“Wonderful to meet you, beautiful Steph,” she said, in her gravelly voice, tinged with a slight Midlands accent.

I was hooked.

“Do you want to go for a walk?” she asked.

“Yes, of course, why not?” I stuttered.

“You can show me around.” She jumped up, took my hand in hers, and pulled me to my feet. She was so strong I almost fell into her. She laughed as she steadied me, though I was tempted to keep falling so she could catch me.

“I was at Yellow Gate when I lived here,” she said.

That figures, I thought. That is where the cool women go.

“I never made it over to Blue. So I don’t know the neighbourhood at all.”

She didn’t let go of my hand as we walked through the bluebells in the spring woods bursting with new life, and told me about her band, her life in Birmingham, her time at Greenham getting arrested and singing at the campfire. She told me how she met the other half of her band, Zephyr, at a WONT (Women Opposed to Nuclear Threat) meeting in the Midlands. They came to Greenham together, Al all in black, Zephyr with her dyed black and white hair teased into a lion’s mane. At the fire, the women sang one of their famous peace songs, and Al and Zephyr began to harmonize, their voices blending above the chorus. They became lovers, wrote songs together in the woods, and plotted to form a band when they got home to their native Birmingham.

“We both loved the Poison Girls and one day we hitched to see them play in Nottingham,” Al said. “A minivan pulled up and we got inside and it was Ranking Roger from the Beat.”

“Oh my God,” I cried. “I love the Beat.”

“Stand Down Margaret, Stand Down Please. Stand Down Margaret,’” Al sang in a deep strong voice, and I soon joined in, and then she was pogo-ing and so was I. We sang the whole song together, from start to finish, collapsing in a laughing heap on the damp grass when we were done.

Al turned to me, brushing some stray hairs back from my face. “Then at the concert we went backstage and we met Vi Subversa, the lead singer of the Poison Girls, and she said, How many songs have you got?’ We said “Three,’ and she said, “You’re opening for me tonight.’”

“That’s so amazing,” I said, also amazed that I was lying on the grass next to her and that her face was so close to mine. I tried not to smile too much, afraid it would make my feelings too obvious.

“Zephyr and I are not together anymore,” Al continued, looking crestfallen, and moved away from me to lie on her back, her hands behind her head. I rolled over onto my back, too, and watched white clouds puff across a blue sky filled with promise. “At least, not as lovers. We are still partners in music. She’s my best friend. And I am still in love with her. But she’s not in love with me. She’s decided she’s more into men.”

“Crazy,” I said, because that was the closest I could come to expressing what I really wanted to say. Is Zephyr nuts? She wants a man when she can have you? I felt disappointed that Al was in love with Zephyr.

Al jumped up, turned to offer me her hand, and pulled me to my feet. We stopped for a split second and looked into each other’s eyes, then she smiled and turned, and offered me her hand. As we walked back toward Blue Gate hand-in-hand, I noticed how Al walked like a bloke, and even looked like a bloke, with the androgynous appearance I was starting to find so compelling in women, the excitement of knowing what was really under her unisex black T-shirt and tight black jeans. She stopped, reached into her pocket, and pulled out a pair of headphones. She placed them on my ears so that I could listen to her singing “Strange Fruit” on her Walkman, the first time I ever heard this sad and moving song about lynchings in the deep south of the United States. Then she played her favourite On the Rag song, “Other Girls Like Me,” where she and Zephyr pelted out lyrics about freedom and women’s rights, Zephyr’s saxophone dancing with Al’s pounding, rhythmic bass: Don’t wanna wear your heels/Don’t wanna cook your meals/Don’t wanna sit on the sidelines/Just want to run, run, run like the boys/Just stop playing with your war toys/Other girls like me/I’m looking for other girls, other girls like me/I’m all right now cos other girls, other girls like me . . .

When the song was done, we continued walking. I told Al that I had just arrived at the camp, that I had studied French and Russian at Bath University, that I cared about apartheid, that I’d had a possessive boyfriend for six years, and that now I was a lesbian. I told her that my family lived a few miles away and that we were not talking, really, and that this part of the world was home to me. I told her that my parents were disappointed with me for choosing to live at the camp, despite their support for Greenham, that they were afraid I was a bad influence on my younger sister, Sarah, who admired me so much she wanted to change her name to mine. I wondered as I told Al this whether Sarah still did.

By the time we made it back to camp, Al’s arm was around my waist, and mine rested on her strong shoulders. When her eyes caught mine as we talked, I was overcome with the desire to throw her to the ground and make crazy love. Instead, I flirted. I found it hard to believe that she was actually interested in me. But she was, and I was alarmed and delighted at the effect she was having on me. We laughed, we told stories, we shared indignation at the horrors of war, the stupidity of nuclear weapons, the all-encompassing damage done by the patriarchy, the cruelty inflicted on animals, and how much better things would be if women were in power, ignoring, for a moment, that Margaret Thatcher was our leader. I learned that Al had the same Scorpio birthday as the first Alison, and I realized, as we crawled into my tent in the middle of the afternoon, that I was about to drop sweet Alison for tough and complicated Al.

We squeezed into the tent, then turned to take off our Doc Martens. You can’t really rip off someone’s Doc Martens in the heat of passion. You can always keep them on . . . but we didn’t, not this time, and instead we struggled with the laces for what felt like an eternity, laughing hysterically and conspiratorially, because we knew what was about to happen and we could barely stand the tension. Finally, they were off, and we closed the tent zip behind us. I turned to face her. She brought her face close to mine and stared into my eyes, then at my lips, then back into my eyes. She placed a finger on my lips and gently traced their contours, humming quietly and deeply to herself. Then she abruptly took my face in her hands and kissed me with more passion than I had ever been kissed before. We undressed each other slowly and playfully, and something woke up in me that I was determined to keep awake.

“Are you sure I’m only your second female lover?” she purred as we lay in each other’s arms two hours later, the tent flap open, our eyes gazing up at the swaying branches with their fresh green leaves and the blue sky above. I felt insanely proud—and I immediately wanted more and pulled her back into the tent, zipping up the flap. Where Alison was gentle, Al was strong. Where Alison was sweet, Al was feisty. She liked to play games and roles and I played along, our imaginations tangling with the leaves above the tent, or the gauze curtains that hung around the bed in her small flat in the Moseley neighbourhood of Birmingham, where she told me, often, that I was beautiful. Martin had never said this to me, and I liked it. I even began to think it might be true. She liked my eyes, my lips, my smile, my body. She liked every part of me, and every part of me liked her back in gratitude. She made sure I enjoyed myself in bed, which to her was a playground, not a battleground, where words were sweet, sexy, and witty, not cruel, unkind, and hurtful.

But Al was busy. While she was mine as often as I could make it to Birmingham, for three nights a week she entertained her other female lover from Newcastle-upon-Tyne, and for two nights, her boyfriend, Rick, an anarcho-punk fan of On the Rag, and a former lover of Zephyr’s. Al managed to keep her three lovers neatly apart for the most part, and it helped that I was busy, too, at the peace camp, too busy to notice, really, that I was far more in love with her than she was with me, and that when she told me that I should never rely on her, I should have taken notice.

Stephanie Davies is a writer who worked for many years in communications for Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) in the United States. A UK native, Stephanie moved to New York in 1991, where she taught English Composition at Long Island University in Brooklyn and led research trips to Cuba. Before moving to New York, she co-edited a grassroots LGBTQ magazine in Brighton called A Queer Tribe. Stephanie earned a French and ESL teaching degree from Aberystwyth University in Wales, and a BA in European Studies from Bath University, England. She grew up in a small rural village in Hampshire, where much of her first book, Other Girls Like Me, takes place. At the age of 22, Stephanie joined a women’s peace camp outside a US military base at Greenham Common in Newbury, a life-changing experience that is at the heart of Other Girls Like Me. Today, Stephanie divides her time between Brooklyn and the Hudson Valley, New York where she lives with her wife, Bea, and rescue dog, Pongo.